My studio practice investigates the history of modern painting with reference to material specificity, application, and pictorial perception. I engage the prospect of uncoupling previous histories from the process of identifying unfamiliar forms. I think of this as an allegory for moving forward in a personal quest to de-stigmatize otherness. In lieu of early twentieth century fourth dimensional antidotes, my work reinvasions the representation of multiple dimensionalities. I’ve re-imagined the pictorial possibilities of a two-dimensional surface. I create paintings that exhibit a distinctive space not dependent upon traditional three-dimensional perspectives. I fracture singular shaped canvases into multiple shapes that relate to each other tangentially. Connected to each-other at points, they shift, lean and pull away from one-anther. At times, voids and linear creases are forged when two adjacent panels are bolted together. I often wonder if it is possible to present a new interpretation of contemporary abstraction with expectations of a different sensibility than that offered by the 1950’s and 60’s, perhaps an alternative worldview of inclusion and historical acceptance.

In all, I construct aesthetics that creates challenging and unconventional viewing experiences. The subjects of these inquiries reflect intentions to politicize abstraction in the interest of suggesting perception as a defining factor in our cultural affair with otherness. The resulting image is subsequently a shaped object on a wall that conveys meaning in its physical presence. It mediates meaningful experiences by fostering curiosity and anxiety in questioning how to approach it.

-Leslie Smith III

In all, I construct aesthetics that creates challenging and unconventional viewing experiences. The subjects of these inquiries reflect intentions to politicize abstraction in the interest of suggesting perception as a defining factor in our cultural affair with otherness. The resulting image is subsequently a shaped object on a wall that conveys meaning in its physical presence. It mediates meaningful experiences by fostering curiosity and anxiety in questioning how to approach it.

-Leslie Smith III

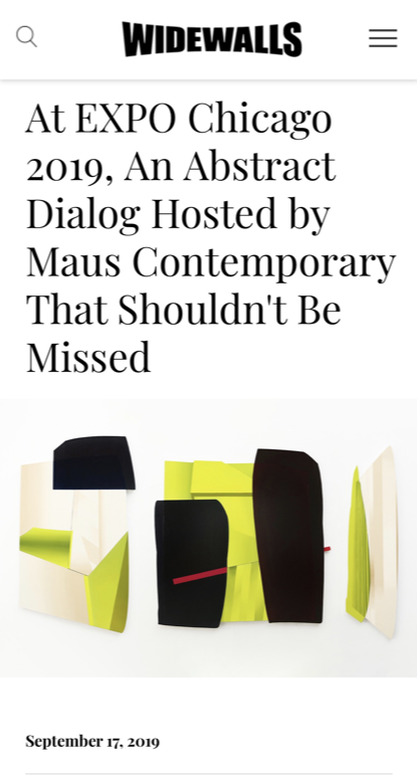

https://www.widewalls.ch/maus-contemporary-expo-chicago-2019-leslie-smith-iii-interview/

Download Full pdf

Download Full pdf

Interview with Bridget Gleeson

www.artsy.net/article/artsy-talking-american-painter-leslie-smith-iii-abstraction-anguish-architecture

Click here for pdf download.

www.artsy.net/article/artsy-talking-american-painter-leslie-smith-iii-abstraction-anguish-architecture

Click here for pdf download.

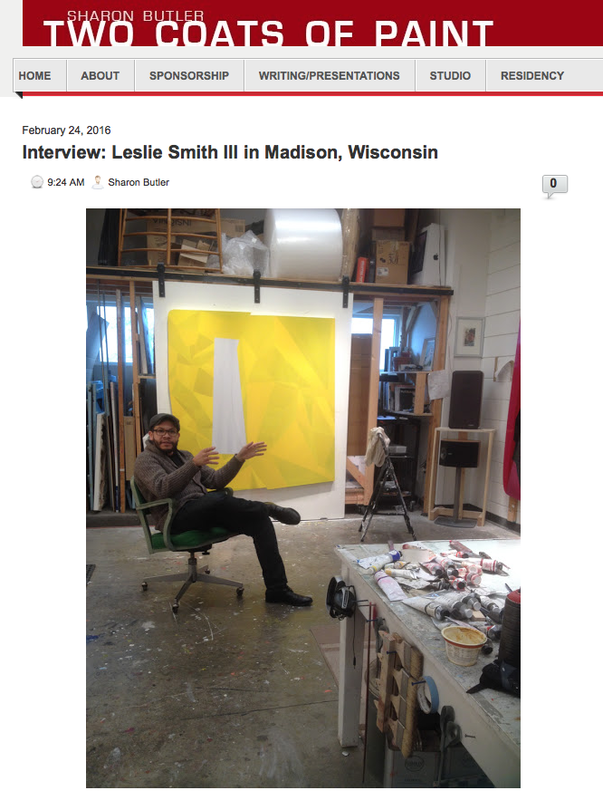

Studio visit interview with Sharon Buttler at Two Coats of Paint,

http://www.twocoatsofpaint.com/2016/02/interview-leslie-smith-iii-in-madison.html

Click here for pdf download

http://www.twocoatsofpaint.com/2016/02/interview-leslie-smith-iii-in-madison.html

Click here for pdf download

Working in monochrome, artists featured in monochromatic push their limits conceptually under restriction of a single color. With roots dating back to the Suprematist Composition in Moscow, monochromatic tradition is an important component of the avant-garde of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Influential to the practice, Color Field painters and Minimalists of the mid- twentieth century, such as Mark Rothko, Ellsworth Kelly and Richard Tuttle, developed single-color use – eventually incorporating shaped canvases. With enduring relevance, execution of artworks using a limited palette (today explored in various mediums) references the long tradition from the past while continuing to prove significant to the present.

The three artists included in triumph & disaster’s monochromatic explore the practice from three different angles. Cameron Martin’s meticulous process presents a contemporary use of traditional landscape, evoking a sense of non-specific nostalgia. Leslie Smith III updates the use of the shaped canvas with paintings showing his understanding of spatial relationships – the restricted color palette allowing the strong and intentional lines of his constructions to serve as the composition. Referencing media of pop culture, Javier Barrios’ cut-mylar collages move between fact and fantasy, confronting the great philosophical questions of mankind.

Artists included: Javier Barrios, Cameron Martin, Leslie Smith III TRIUMPH & DISASTER, www.triumphdisastergallery.com

WORDS Caroline Taylor

The three artists included in triumph & disaster’s monochromatic explore the practice from three different angles. Cameron Martin’s meticulous process presents a contemporary use of traditional landscape, evoking a sense of non-specific nostalgia. Leslie Smith III updates the use of the shaped canvas with paintings showing his understanding of spatial relationships – the restricted color palette allowing the strong and intentional lines of his constructions to serve as the composition. Referencing media of pop culture, Javier Barrios’ cut-mylar collages move between fact and fantasy, confronting the great philosophical questions of mankind.

Artists included: Javier Barrios, Cameron Martin, Leslie Smith III TRIUMPH & DISASTER, www.triumphdisastergallery.com

WORDS Caroline Taylor

Walter Lewellyn "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood"

LESLIE SMITH TAKES THE LEAD IN BETA PICTORIS SHOW OF ABSTRACT PAINTINGS.

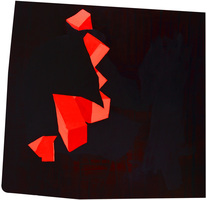

"Lay Away" Oil on Shaped Canvas, 2013

"Lay Away" Oil on Shaped Canvas, 2013

The French poet Michel Deguy once wrote that, “Poetry, like love, risks everything on signs.” In a similar sense, the problem with abstract art is that it’s abstract. Any piece of art that an abstract artist begins work on necessarily has to be finished by the many viewers who look at it, changing its meaning with each fresh perspective.

That’s the struggle that abstract painter Leslie Smith III is dealing with in his first solo show at downtown’s beta pictoris gallery, As I Remembered. A professor at the University of Wisconsin’s art department, Smith admits to an unfashionable desire to have his personal inspiration bleed through to the viewer, creating fascinating, inventive tensions in his work.

Smith works almost entirely in blues, oranges, and shades of gray, butAs I Remembered is anything but simple or remote. The unusual shapes of the canvases, the dance between strict geometric figures and impressionistic blurs, and the color and interplays of light lurking under coats of black paint all give the sense that the paintings are somehow reaching out to the audience. Though never overtly political, Smith’s paintings do challenge the viewer to make up his or her mind on their meaning.

Even though it can seem faintly unbalancing for the viewer, the exhibition can be soothing, too. Like former beta pictoris artist Pete Schulte, Smith’s darker works are often warm, inviting and human, and the show as a whole has internal callbacks that make it feel like the paintings are in dialogue with each other. For instance, a study of different orange shapes in Honest Boy, a playful not-quite-Cubist representation of Pinocchio, is mirrored across the gallery in the massive Lay Away, which features vivid orange figures clawing out of a black canvas — or being sucked into the quagmire.

The dialogue is rooted in a sense of character and scene, as Smith creates dramas out of the power dynamics of human relationships. His messages are subtle and very much open to interpretation, but they’re undeniably present, lurking beneath each surface diversion in Smith’s paintings, many of them rooted in emotional pain.

Smith’s work reveals a profound, but nuanced, sense of control, whether it’s exploring the domination to which people subject one another, or whether it’s Smith’s own yearning to be understood. Rather than inklings of suggestions of ideas, he wants to communicate exactly what he (or his characters) were experiencing when he painted each work, transporting the viewer to an emotional prism where Smith’s memories are recreated in stunning games of shape and color.

That’s the struggle that abstract painter Leslie Smith III is dealing with in his first solo show at downtown’s beta pictoris gallery, As I Remembered. A professor at the University of Wisconsin’s art department, Smith admits to an unfashionable desire to have his personal inspiration bleed through to the viewer, creating fascinating, inventive tensions in his work.

Smith works almost entirely in blues, oranges, and shades of gray, butAs I Remembered is anything but simple or remote. The unusual shapes of the canvases, the dance between strict geometric figures and impressionistic blurs, and the color and interplays of light lurking under coats of black paint all give the sense that the paintings are somehow reaching out to the audience. Though never overtly political, Smith’s paintings do challenge the viewer to make up his or her mind on their meaning.

Even though it can seem faintly unbalancing for the viewer, the exhibition can be soothing, too. Like former beta pictoris artist Pete Schulte, Smith’s darker works are often warm, inviting and human, and the show as a whole has internal callbacks that make it feel like the paintings are in dialogue with each other. For instance, a study of different orange shapes in Honest Boy, a playful not-quite-Cubist representation of Pinocchio, is mirrored across the gallery in the massive Lay Away, which features vivid orange figures clawing out of a black canvas — or being sucked into the quagmire.

The dialogue is rooted in a sense of character and scene, as Smith creates dramas out of the power dynamics of human relationships. His messages are subtle and very much open to interpretation, but they’re undeniably present, lurking beneath each surface diversion in Smith’s paintings, many of them rooted in emotional pain.

Smith’s work reveals a profound, but nuanced, sense of control, whether it’s exploring the domination to which people subject one another, or whether it’s Smith’s own yearning to be understood. Rather than inklings of suggestions of ideas, he wants to communicate exactly what he (or his characters) were experiencing when he painted each work, transporting the viewer to an emotional prism where Smith’s memories are recreated in stunning games of shape and color.

Leah Kolb "Paintings in Conflict: Leslie Smith’s Contemporary Abstractions"

Red Light

Red Light

The death knell for painting sounded by Douglas Crimp in 1981 was less a true indication of the medium’s demise than of a crisis in discourse.[1] Crimp admonished painting for its inward-looking focus, which, he argued, had rendered it incapable of functioning in the essential capacity of critique. Three years later, Arthur Danto made an even bolder statement, declaring the end of art itself, by which he meant the end of western art’s narrative of linear progress.[2] Sensing a changed art-world context, Danto and Crimp, among other theorists, signaled the emergence of a new era of contemporary art thinking and making. This change initiated a culture of critique that remains a relevant challenge to many contemporary artists, particularly painters, who are obligated to respect their medium’s legacy while also recognizing its diminished status.

While some choose to sidestep the formidable baggage associated with painting and painted abstraction, Leslie Smith III confronts this history and its attendant dogmas. With a graduate degree from the acclaimed Yale University School of Art, Smith admits that the entrenched discourse surrounding his practice is ingrained in his thinking, that “it will always be a part of the mix.” He freely assimilates these conversations, but creates works that collapse the medium’s traditional divisions. In doing so, he seems to suggest that contemporary abstract painting can critically engage its rich history while also transcending its ideological limitations; that the so-called death of art was really just a way to establish new conditions for its inevitable survival. This practice results in work that does not echo the past, but instead remains strongly rooted in and relevant to contemporary life.

Inherent in this negotiation, however, is a certain unease, which is visually and conceptually manifested in Smith’s work. In discussing his practice, he has stated that the impetus for his paintings emerges from a place of friction, “from a need to analyze conflicting realities evident in how we, as a society, relate to each other.” Smith grapples with the complexity of human interaction and power relationships in Red Light [plate 2], for example, which pictures a woman’s shapely crossed legs, a curved pipe hooked around her left ankle. The solid metal of the pipe is countered by a flaccid, crimson lump draped over the woman’s thigh. Though the scene is enigmatic, it exudes a palpable anxiety and tension. The saturated red-on-red color heightens the emotional and psychological intensity, which is compounded by the sexual dynamics of erotic dominance versus impotence. If his abstracted imagery suggests a poetics of human conflict, Smith’s paintings are also self-reflective; they address and even embody the perceived binaries, or clashes, within the medium of painting: the hierarchical past in contrast to the unwieldy present, representation as opposed to abstraction, and expressive gesture versus formal purity.

While some choose to sidestep the formidable baggage associated with painting and painted abstraction, Leslie Smith III confronts this history and its attendant dogmas. With a graduate degree from the acclaimed Yale University School of Art, Smith admits that the entrenched discourse surrounding his practice is ingrained in his thinking, that “it will always be a part of the mix.” He freely assimilates these conversations, but creates works that collapse the medium’s traditional divisions. In doing so, he seems to suggest that contemporary abstract painting can critically engage its rich history while also transcending its ideological limitations; that the so-called death of art was really just a way to establish new conditions for its inevitable survival. This practice results in work that does not echo the past, but instead remains strongly rooted in and relevant to contemporary life.

Inherent in this negotiation, however, is a certain unease, which is visually and conceptually manifested in Smith’s work. In discussing his practice, he has stated that the impetus for his paintings emerges from a place of friction, “from a need to analyze conflicting realities evident in how we, as a society, relate to each other.” Smith grapples with the complexity of human interaction and power relationships in Red Light [plate 2], for example, which pictures a woman’s shapely crossed legs, a curved pipe hooked around her left ankle. The solid metal of the pipe is countered by a flaccid, crimson lump draped over the woman’s thigh. Though the scene is enigmatic, it exudes a palpable anxiety and tension. The saturated red-on-red color heightens the emotional and psychological intensity, which is compounded by the sexual dynamics of erotic dominance versus impotence. If his abstracted imagery suggests a poetics of human conflict, Smith’s paintings are also self-reflective; they address and even embody the perceived binaries, or clashes, within the medium of painting: the hierarchical past in contrast to the unwieldy present, representation as opposed to abstraction, and expressive gesture versus formal purity.

Speak Up

Speak Up

When Arthur Danto declared the end of art, he did not mean the end of all artistic production, but rather the end of a specific kind of art-historical thinking. He suggested that what marks contemporary art as truly contemporary is its absolute lack of a definable style. If anything can be art, then there can be no overarching narrative and thus no clear path forward.[3] As such, the question remains: where do contemporary artists locate themselves within and in relation to the post-historical art world? One might argue that this unanswerable question informs the greater context of conflict in Smith’s work. Smith also addresses the effect of critical discourse on the artist. In Speak Up [plate 1], the loosely articulated central form can be perceived as a human figure, hunched before an imposing array of microphones. Although gauzy white paint strokes shroud the figure from a prying public, the title of the painting demands revelation. Further, the work implicates us as viewers. As microphone-wielding interrogators, we implore answers to much larger questions about the role, responsibility, and relevance of contemporary painting today. Although Smith’s work invokes questions concerning the essence of contemporary art, the painting’s implied silence rejects the possibility of an answer.

You First

You First

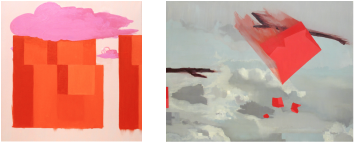

In other words, our current art world opens up the practice of painting by breaking down Modernism’s traditional and essentialist categories of art. By moving beyond a reductive vision of art-making, the long-standing wedge separating representational art from abstraction, and formal purity from expressive gesture, can be removed. And, given the latitude to not “speak up” or follow a single stylistic direction, Smith is able to pursue a more flexible practice of painterly invention, while also refusing to resolve the tensions and uncertainties that result. You First [plate 4], for example, suggests a figurative presence through simple shapes and painterly lines, and like Speak Up, the work flirts with recognizable form. In the painting, two bright-red, boxy structures, each partially eclipsed by a smaller circular form and topped by a mop of black spiraling lines, occupy opposite edges of the canvas. When trying to make sense of the imagery, we cannot help but anthropomorphize this grouping of basic shapes: boxes transform into faces, spheres becomes noses, and chaotic lines morph into curly hair. The work is neither purely abstract nor clearly representational, and this ambiguity reflects the freedom, Smith claims, to “consciously make paintings that deny categorization.”

"Self" & "Stick, Stones, or Drones"

(left to right)

"Self" & "Stick, Stones, or Drones"

(left to right)

Smith thus creates works that vacillate between seemingly irresolvable perceptions. The notion of floating between spaces is visualized in two additional works from 2012: Self and Sticks, Stones, or Drones [plates 3 and 5]. In each painting, cubed figures are suspended in the middle of the canvas, hovering in a nebulous zone. If we can understand these boxy characters as allegorically personifying the artist himself, as he has stated, then his paintings mirror his relationship to the larger world. By extension, Smith finds himself occupying a liminal space, an allusion to the current state of painted abstraction, where the absence of a grand narrative pushes art-making into a boundless free float.

"Night Twitch" & "Night Baptism"

(left to Right)

"Night Twitch" & "Night Baptism"

(left to Right)

Without clear direction forward, with no defined (or definable) trajectory to follow, Smith’s most recent paintings appropriately echo the disorientation of forging a path through uncertain terrain. In Night Twitch and Night Baptism [plates 11 and 14], Smith wanted to “use the tools of painting to express how we see darkness.” Like his other work, Smith’s black paintings are rooted in both worldly and aesthetic conflict. Inspired by a personal event, Night Baptism speaks to the contradictions of organized religion. Simple ovular shapes coalesce to form the rough outline of a contorted figure standing in a murky pool of blackness—a stark contrast to the spiritual purity symbolized by the baptismal ceremony. If its title and subject matter suggest religious hypocrisy, the painting’s aesthetic qualities also reinforce the notion of duplicity. Because the painting is literally sheathed in black, Smith’s expressive use of surface texture holds heightened significance: the gesture of the brush strokes contradicts the suggested movement of the figure, and the reflective sheen of one black pigment contrasts with the flat matte of the other. Even the shape of the canvas adds visual dissonance; rather than conforming to the square or rectangle of a standard stretcher, it hangs slightly askew with its left corners rounded. All of Smith’s paintings from 2013 sit on similarly shaped canvases, each with an edge that swells outwards as if attempting to break away from the stretcher’s underlying structure. The irregular shape of the canvases is an appropriate complement to an art world where the practice of painting is unstructured, no longer bound by historical traditions or predetermined categories.

The visual dualities in Smith’s paintings reinforce the narrative content of human discord. In other words, his paintings are both about conflict and in conflict. Ideas in paint reflect ideas about paint, resulting in works that are intrinsically tied to their existence as paintings. In the case of Leslie Smith III, the paintings reflect a certain sensibility of the present, draw from the uneasy social dynamics of human relationships, and function as a point of departure for a broader discussion about the uncertainty surrounding the practice of contemporary abstract painting.

[1] Crimp, Douglas. “The End of Painting.” October 16 (1981): 69–86.

[2] Danto, Arthur. “The End of Art.” In The Death of Art. New York: Haven Publications, 1984

[3] Danto, Arthur. After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997

Leah Kolb

Associate Curator

Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

The visual dualities in Smith’s paintings reinforce the narrative content of human discord. In other words, his paintings are both about conflict and in conflict. Ideas in paint reflect ideas about paint, resulting in works that are intrinsically tied to their existence as paintings. In the case of Leslie Smith III, the paintings reflect a certain sensibility of the present, draw from the uneasy social dynamics of human relationships, and function as a point of departure for a broader discussion about the uncertainty surrounding the practice of contemporary abstract painting.

[1] Crimp, Douglas. “The End of Painting.” October 16 (1981): 69–86.

[2] Danto, Arthur. “The End of Art.” In The Death of Art. New York: Haven Publications, 1984

[3] Danto, Arthur. After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997

Leah Kolb

Associate Curator

Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

Katherine Murrell "Leslie Smith III: Representation, Abstraction, Oscillation"

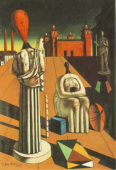

The Disquieting Muses, Georgio De Chirico

The paintings of Leslie Smith III are a synthesis of creation and suggestion, fluidly moving between imagination and reality. Their bold forms and extroverted colors have an easy appeal, yet retain a deep-seated spark of mystery, an enigmatic soul whose essential and symbolic self is not easily given away.

Smith sees painting as a physical process. He has a background as a classically trained painter, but embraces energy and ambiguities traced to expressionist practices. Drawing from all values on the spectrum of representation, a palpable tension is generated as his works oscillate between abstraction and overt likenesses of the physical world. Equally integral to his oeuvre is the insinuation of psychological underpinnings, where the human condition is manifest by inanimate objects and narrative possibilities, though rarely reaching definite resolutions.

Taking in the selection of recent paintings as seen in this exhibition, the viewer will become aware of recurring motifs and structures. Color plays a role in shaping the emotional stage of a composition, particularly in the arrangement of hot shimmering hues against cooler or neutral grounds. Vibrant forms command the eye, taking on roles as leading characters with dramatic overtones. Ambiguous and amorphous forms claim the spotlight, positioned close to the front of the picture plane. Smith balances space and flatness through the noncommittal shaping of his background, but the main figures at play are frequently treated with eloquent details indicating depth and texture, both in visual styling and the physical treatment of the canvas surface.

Certain images become more than details of rooms or quotations of landscape, taking on roles as active narrative agents. Tendrils of conflict thread through these paintings, rarely in an overt manner, yet their treatment suggests something happening beneath the surface of our immediate understanding. In How Long Has This Been Going On an arched space is punctuated by luminously glowing orbs. The framing of the space irresistibly suggests a window, which is a frequent player in the world of Smith’s paintings. But which window, and which night? Are we witnessing a mystical snowfall, the vastness of a starry sky, or perhaps diffused lights through fog? Dimensional cues are given through steady highlights on sticks and the gossamer billowing of curtains. On the ledge in front of us, a bound, white cloth beckons. Smith tantalizes with clues but remains aloof, insistent on the viewer as a conduit for establishing meaning while he purposefully nudges us in directions of melancholy or unease, thoughtfulness or tension.

Characters such as the branches and orb-filled sky appear in other compositions, notably the equally mysterious I Dream Too Much. Similarly, the window appears in other settings, though not always with the same styling. In Creeper we are faced with the arched shape, a window or a passage in blocked pink shapes. More immediately before us looms something like an animate, droplet-speckled being. In this instance, Smith directly invokes the tradition of figure painting in the foreground, but it is a secondary emphasis, providing a counterpoint for the unknown implications of the mysterious being at the center of the composition.

Viennese Waltz includes detail that harkens to earlier works through the use of pattern. Contrasting masses, rounded and blocked, circle each other in a unique dance. Underneath lies an ornate passage, dimensional and sumptuous, conceived as a brocade surface ready to slip away. It is pinned underneath the weight of its companion shapes, its own trajectory thwarted. The fine detail coalesces from afar yet upon close inspection, the motif loosens into delicate, thin rivulets, eternally suspended. It is a piece rich with nuance as firm, round passages exist in dynamic contrast with hard-edge geometries and airy pattern.

While Smith is a thoroughly contemporary artist, he possesses sensibilities that recall past masters. The Pittura Metafisica of Giorgio de Chirico is a tendency to which Smith gives a nod, particularly in the manner of composing an alternate space that is related to, yet distinct from, reality. De Chirico, an artist admired by the Surrealists of the early 20th century, skillfully juxtaposed forms of classical architecture with shifting and dramatic contrasts of light and color. Similarly, Smith commandingly employs the possibilities of the painter’s toolbox to create works with a conscious sense of displacement, like the transcript of a waking dream.

The value of Smith’s bold forms and their presence as monumental canvases is not realized by only a cursory glance. The unfolding of each piece takes place over time, and requires a thoughtful investment from the viewer to absorb the conditions of metaphor. Entrancing color combinations and seemingly familiar forms are ultimately revealed to be moments for mediation. His paintings shift between the physicality of paint and the psychology of suggestion, the play of aesthetics and formal concerns, and the possibilities of interior, intimate stories.

Katherine Murrell

Lecturer in Art History

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design

Smith sees painting as a physical process. He has a background as a classically trained painter, but embraces energy and ambiguities traced to expressionist practices. Drawing from all values on the spectrum of representation, a palpable tension is generated as his works oscillate between abstraction and overt likenesses of the physical world. Equally integral to his oeuvre is the insinuation of psychological underpinnings, where the human condition is manifest by inanimate objects and narrative possibilities, though rarely reaching definite resolutions.

Taking in the selection of recent paintings as seen in this exhibition, the viewer will become aware of recurring motifs and structures. Color plays a role in shaping the emotional stage of a composition, particularly in the arrangement of hot shimmering hues against cooler or neutral grounds. Vibrant forms command the eye, taking on roles as leading characters with dramatic overtones. Ambiguous and amorphous forms claim the spotlight, positioned close to the front of the picture plane. Smith balances space and flatness through the noncommittal shaping of his background, but the main figures at play are frequently treated with eloquent details indicating depth and texture, both in visual styling and the physical treatment of the canvas surface.

Certain images become more than details of rooms or quotations of landscape, taking on roles as active narrative agents. Tendrils of conflict thread through these paintings, rarely in an overt manner, yet their treatment suggests something happening beneath the surface of our immediate understanding. In How Long Has This Been Going On an arched space is punctuated by luminously glowing orbs. The framing of the space irresistibly suggests a window, which is a frequent player in the world of Smith’s paintings. But which window, and which night? Are we witnessing a mystical snowfall, the vastness of a starry sky, or perhaps diffused lights through fog? Dimensional cues are given through steady highlights on sticks and the gossamer billowing of curtains. On the ledge in front of us, a bound, white cloth beckons. Smith tantalizes with clues but remains aloof, insistent on the viewer as a conduit for establishing meaning while he purposefully nudges us in directions of melancholy or unease, thoughtfulness or tension.

Characters such as the branches and orb-filled sky appear in other compositions, notably the equally mysterious I Dream Too Much. Similarly, the window appears in other settings, though not always with the same styling. In Creeper we are faced with the arched shape, a window or a passage in blocked pink shapes. More immediately before us looms something like an animate, droplet-speckled being. In this instance, Smith directly invokes the tradition of figure painting in the foreground, but it is a secondary emphasis, providing a counterpoint for the unknown implications of the mysterious being at the center of the composition.

Viennese Waltz includes detail that harkens to earlier works through the use of pattern. Contrasting masses, rounded and blocked, circle each other in a unique dance. Underneath lies an ornate passage, dimensional and sumptuous, conceived as a brocade surface ready to slip away. It is pinned underneath the weight of its companion shapes, its own trajectory thwarted. The fine detail coalesces from afar yet upon close inspection, the motif loosens into delicate, thin rivulets, eternally suspended. It is a piece rich with nuance as firm, round passages exist in dynamic contrast with hard-edge geometries and airy pattern.

While Smith is a thoroughly contemporary artist, he possesses sensibilities that recall past masters. The Pittura Metafisica of Giorgio de Chirico is a tendency to which Smith gives a nod, particularly in the manner of composing an alternate space that is related to, yet distinct from, reality. De Chirico, an artist admired by the Surrealists of the early 20th century, skillfully juxtaposed forms of classical architecture with shifting and dramatic contrasts of light and color. Similarly, Smith commandingly employs the possibilities of the painter’s toolbox to create works with a conscious sense of displacement, like the transcript of a waking dream.

The value of Smith’s bold forms and their presence as monumental canvases is not realized by only a cursory glance. The unfolding of each piece takes place over time, and requires a thoughtful investment from the viewer to absorb the conditions of metaphor. Entrancing color combinations and seemingly familiar forms are ultimately revealed to be moments for mediation. His paintings shift between the physicality of paint and the psychology of suggestion, the play of aesthetics and formal concerns, and the possibilities of interior, intimate stories.

Katherine Murrell

Lecturer in Art History

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design

Interview with Russell Panczenko-Director of the Chazen Museum of Art

Erica Agyeman "Medium and The Message "

International Review of African American Art Vol. 23 No. 4

(December 2011): 35-38

You’ve had this conversation before: Nice to meet you. You’re an artist? What kind? A sculptor. A photographer. A performance artist. Even when these labels don’t quite fit – a painter, who has recently been working with sound – the response will invariably be related to the medium of the work.

The tendency to begin vernacular and formal classifications of art and an artist’s practice through their medium makes sense in light of recent art history. Modernism’s concern with the nature of specific mediums and postmodernism’s introduction of high-low pastiche have positioned the medium as the point of origin for classifying art-making and art makers. While the thingly qualities of art are indubitably as important now as in the past, classifying artwork in terms of the medium also classifies the artist’s process in these terms. Do these classifications still fit the way that artists work in the present?

At the 2009 Tate Britain triennial, curator Nicholas Bourriard introduced the term “altermodern” to describe today’s art and artistic processes. Bourriard sees contemporary art not as an object, but as a network or trajectory. He describes his concept through the term “hypertext,” a sequence of interconnected forms in which artists work as “cultural nomads” exploring space, time, and signs. He created a new term, “homo viator,” from the Latin word for “traveler,” to replace “artist.” For Bourriard, the medium of all art today is asequence.

Leslie Smith III and Tim Roseborough use common forms of communication to enhance the interactivity of a viewer with sequences of signs motivated by, and embedded in, their prospective works. It is what drew curator Tod Roulette to select their works for an exhibition at Strivers Gardens Gallery in Harlem, New York; October 27 to December 31, 2011. Roulette sees these sequences of signs in Smith and Roseborough’s works as “visual code” that interactively engages the viewer.

Smith uses a series of object-characters to enact dimensions of psychological tension in his oil paintings. Roseborough’s prints translate selections of text printed in an illegible alphabet, encrypting the legibility of the text but hinting at its meaning through other elements such as color. Roulette says: “I love that he (Roseborough) uses colors that we African Americans think we understand. But then if you look at them, there is so much more to them.”

Is it computer code? Some kind of blueprint? Or perhaps some version of the black and white square QR codes so prevalent today? Tim Roseborough’s recent works come predominantly through the invention of his Englyph writing system. Inspired by the shapes of the letters of the Latin alphabet, his abstracted shapes are nestled one inside the other to form words and sentences consistent with the structure of the English language. It is in some ways similar to the processes utilized by data visualization artists, but in Roseborough’s case he is re-processing the linguistic structures through which the data is understood. He said “I am taking something that is clear to those who can understand the English language and ‘re-obfuscating’ it, taking our familiar language and making it unfamiliar.” His illegible Englyph complicates a common form of communication and draws attention to the structures and processes of that type of exchange. In his recent Englyph project for Art In America magazine (2011) Roseborough wrote, “I saw words as too closely tethered to their meaning, often lacking any fresh sense of the visual.” His use of illegible Englyph subverts the viewer’s ability to comprehend textual meaning and instead focuses on the meaning-value accumulated through other visual characteristics, such as color. This is especially powerful in his recent Englyph prints, Show me the race… whose red, green, and black colors unequivocally communicate a sense of black empowerment. The prints are iterations of his complete artwork, accessible online as a website, www.panafrican.com.

For Roseborough, the medium of his work is a website. It’s online format permits the kind of interactivity that animates his concepts for viewers (or perhaps more appropriately users). He uses this format in order “to expand the reach of the themes and concepts that I want to express,” rather than comment upon the medium itself. It is a practice unlike “glitch art, which seeks to exploit and bring attention to the paradigms of the online medium.” Roseborough’s digital medium is simply his raw material.

Analyzing the historical process of signification of the red-green-black chromatic triad is at the heart of Roseborough’s online work,Pan African. The website includes Roseborough’s Englyph translations, a music video, and historical ephemera which interactively engage the viewer to consider the temporal transformation and cultural signification of these three colors through a series of historical events. He uses interactive components such as rollovers, where the user can move the mouse across the screen and reveal Englyph-English translations of the Garvey quote and subtitles to the music video to both encrypt and decode the significance of the historical material. It is an interactive and processual experience.

For an online artist like Roseborough, the medium is easy to rectify with Bourriard’s Altermodern concept. After all, the viewer experience is in itself a sequence of choices, self guided hypertext, as the user determines their own journey through a sequence of interactions, clicking on one page to the next. But how does this idea function within something like painting?

Over the last six years, Yale MFA graduate Leslie Smith III’s painting practice has moved away from the pictoral forms of his earlier work, and moved toward a mode that “requires more investment from the viewer.” He explains: “Ultimately, I really strive to create an image, an object, a painting, whatever you want to call it, that encourages a participatory experience, so it’s not just a one way street.” Smith, like Roseborough is heavily invested in engaging viewer interactivity through common forms of communication. Smith says, “I look at a lot of film, TV, sitcoms, contemporary narratives that vibe off how people understand things.” He uses these tools and tropes to introduce a familiar experience to the viewer, “so people will know how to respond to the paintings. They may not think they are responding to them, but they are responding to them…very similarly to the way they are to that billboard or that big building on Avenue of the Americas on Canal Street.”

Smith initiates this familiarity and interactivity by sparking the viewer’s curiosity compositionally, through visual voids. He describes these voids as disruptions of a classical narrative, wherein characters would normally engage with each other and the viewer observes from beyond the four edges of the canvas. “What happens when you paint one of the characters out and the viewer is made aware of that void because something is missing...and that something is themselves?”

Window’s deceptively simple design and smaller size (24 x 24 in) makes the effectiveness of his technique noteworthy. In this work, wind blows a diaphanous curtain through a window while a speckled metallic light shines in from outside enlivening the interior space with color. The visual void that Smith has created is alluded to simply by the reach of the curtain projecting from the window, attempting to bridge the physical space between painted object and viewer. (It is a compositional technique similar to that of the microphones in Speak Up.) The quality of the paint, the surface’s glistening candied cherry red and deep black matte are really what make these techniques work. Simultaneously absorbent and reflective, airy and heavy, the light and spaces of Smith’s Window tease and entice the viewer into its uncertain space.

The organic, curved shape of the window reappears in several of Smith’s new works, as does the cloth curtain though in the form of a veil or shroud, ear buds, microphones, and other new additions to his lexicon. His use of repeating character-objects layer and deepen the viewer’s experience with them. It is reminiscent of Philip Guston’s repeated use of boots and Ku Klux Klan hoods, but in Smith’s case he frequently chooses objects that are inert and relatively benign. The objects become characters through his manipulation of them within in the compositions, animated and charged by their interaction with the viewer. This is the fundamental basis for Smith’s work. “I use objects and arrange space and position these things together. The curiosity that comes out of that, allows for the viewer to be able to come to terms with what the painting means to them. That is indicative of the experience that one would have with a lot of images, but in this case it becomes the impetus. Not just of the image, but of the experience, what is most important, and what drives the experience.”

The concept of network as introduced by Bourriard’s altermodern, posits that all art today is created as a series or sequence of signs. While it is difficult to accept a singular term to define all contemporary art today, altermodern’s expansive definition makes it an attractive possibility. Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art curator, Naomi Beckwith, surmises that the concept of medium as a network is best considered as an attempt to “de-center the artwork, not as the end of a set of aesthetic decisions, but one of the many things that come out of a certain set of processes.” It is shift in classification that appropriately respects the importance of interactive and process oriented engagement with signs in artwork by Roseborough and Smith.

Tim Roseborough is based in San Francisco. Leslie Smith is an assistant professor of painting and drawing at the University of Wisconsin (Madison).

Erica Agyeman is graduate student in Modern Art History Critical and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University.

erica.agyeman@gmail.com

The tendency to begin vernacular and formal classifications of art and an artist’s practice through their medium makes sense in light of recent art history. Modernism’s concern with the nature of specific mediums and postmodernism’s introduction of high-low pastiche have positioned the medium as the point of origin for classifying art-making and art makers. While the thingly qualities of art are indubitably as important now as in the past, classifying artwork in terms of the medium also classifies the artist’s process in these terms. Do these classifications still fit the way that artists work in the present?

At the 2009 Tate Britain triennial, curator Nicholas Bourriard introduced the term “altermodern” to describe today’s art and artistic processes. Bourriard sees contemporary art not as an object, but as a network or trajectory. He describes his concept through the term “hypertext,” a sequence of interconnected forms in which artists work as “cultural nomads” exploring space, time, and signs. He created a new term, “homo viator,” from the Latin word for “traveler,” to replace “artist.” For Bourriard, the medium of all art today is asequence.

Leslie Smith III and Tim Roseborough use common forms of communication to enhance the interactivity of a viewer with sequences of signs motivated by, and embedded in, their prospective works. It is what drew curator Tod Roulette to select their works for an exhibition at Strivers Gardens Gallery in Harlem, New York; October 27 to December 31, 2011. Roulette sees these sequences of signs in Smith and Roseborough’s works as “visual code” that interactively engages the viewer.

Smith uses a series of object-characters to enact dimensions of psychological tension in his oil paintings. Roseborough’s prints translate selections of text printed in an illegible alphabet, encrypting the legibility of the text but hinting at its meaning through other elements such as color. Roulette says: “I love that he (Roseborough) uses colors that we African Americans think we understand. But then if you look at them, there is so much more to them.”

Is it computer code? Some kind of blueprint? Or perhaps some version of the black and white square QR codes so prevalent today? Tim Roseborough’s recent works come predominantly through the invention of his Englyph writing system. Inspired by the shapes of the letters of the Latin alphabet, his abstracted shapes are nestled one inside the other to form words and sentences consistent with the structure of the English language. It is in some ways similar to the processes utilized by data visualization artists, but in Roseborough’s case he is re-processing the linguistic structures through which the data is understood. He said “I am taking something that is clear to those who can understand the English language and ‘re-obfuscating’ it, taking our familiar language and making it unfamiliar.” His illegible Englyph complicates a common form of communication and draws attention to the structures and processes of that type of exchange. In his recent Englyph project for Art In America magazine (2011) Roseborough wrote, “I saw words as too closely tethered to their meaning, often lacking any fresh sense of the visual.” His use of illegible Englyph subverts the viewer’s ability to comprehend textual meaning and instead focuses on the meaning-value accumulated through other visual characteristics, such as color. This is especially powerful in his recent Englyph prints, Show me the race… whose red, green, and black colors unequivocally communicate a sense of black empowerment. The prints are iterations of his complete artwork, accessible online as a website, www.panafrican.com.

For Roseborough, the medium of his work is a website. It’s online format permits the kind of interactivity that animates his concepts for viewers (or perhaps more appropriately users). He uses this format in order “to expand the reach of the themes and concepts that I want to express,” rather than comment upon the medium itself. It is a practice unlike “glitch art, which seeks to exploit and bring attention to the paradigms of the online medium.” Roseborough’s digital medium is simply his raw material.

Analyzing the historical process of signification of the red-green-black chromatic triad is at the heart of Roseborough’s online work,Pan African. The website includes Roseborough’s Englyph translations, a music video, and historical ephemera which interactively engage the viewer to consider the temporal transformation and cultural signification of these three colors through a series of historical events. He uses interactive components such as rollovers, where the user can move the mouse across the screen and reveal Englyph-English translations of the Garvey quote and subtitles to the music video to both encrypt and decode the significance of the historical material. It is an interactive and processual experience.

For an online artist like Roseborough, the medium is easy to rectify with Bourriard’s Altermodern concept. After all, the viewer experience is in itself a sequence of choices, self guided hypertext, as the user determines their own journey through a sequence of interactions, clicking on one page to the next. But how does this idea function within something like painting?

Over the last six years, Yale MFA graduate Leslie Smith III’s painting practice has moved away from the pictoral forms of his earlier work, and moved toward a mode that “requires more investment from the viewer.” He explains: “Ultimately, I really strive to create an image, an object, a painting, whatever you want to call it, that encourages a participatory experience, so it’s not just a one way street.” Smith, like Roseborough is heavily invested in engaging viewer interactivity through common forms of communication. Smith says, “I look at a lot of film, TV, sitcoms, contemporary narratives that vibe off how people understand things.” He uses these tools and tropes to introduce a familiar experience to the viewer, “so people will know how to respond to the paintings. They may not think they are responding to them, but they are responding to them…very similarly to the way they are to that billboard or that big building on Avenue of the Americas on Canal Street.”

Smith initiates this familiarity and interactivity by sparking the viewer’s curiosity compositionally, through visual voids. He describes these voids as disruptions of a classical narrative, wherein characters would normally engage with each other and the viewer observes from beyond the four edges of the canvas. “What happens when you paint one of the characters out and the viewer is made aware of that void because something is missing...and that something is themselves?”

Window’s deceptively simple design and smaller size (24 x 24 in) makes the effectiveness of his technique noteworthy. In this work, wind blows a diaphanous curtain through a window while a speckled metallic light shines in from outside enlivening the interior space with color. The visual void that Smith has created is alluded to simply by the reach of the curtain projecting from the window, attempting to bridge the physical space between painted object and viewer. (It is a compositional technique similar to that of the microphones in Speak Up.) The quality of the paint, the surface’s glistening candied cherry red and deep black matte are really what make these techniques work. Simultaneously absorbent and reflective, airy and heavy, the light and spaces of Smith’s Window tease and entice the viewer into its uncertain space.

The organic, curved shape of the window reappears in several of Smith’s new works, as does the cloth curtain though in the form of a veil or shroud, ear buds, microphones, and other new additions to his lexicon. His use of repeating character-objects layer and deepen the viewer’s experience with them. It is reminiscent of Philip Guston’s repeated use of boots and Ku Klux Klan hoods, but in Smith’s case he frequently chooses objects that are inert and relatively benign. The objects become characters through his manipulation of them within in the compositions, animated and charged by their interaction with the viewer. This is the fundamental basis for Smith’s work. “I use objects and arrange space and position these things together. The curiosity that comes out of that, allows for the viewer to be able to come to terms with what the painting means to them. That is indicative of the experience that one would have with a lot of images, but in this case it becomes the impetus. Not just of the image, but of the experience, what is most important, and what drives the experience.”

The concept of network as introduced by Bourriard’s altermodern, posits that all art today is created as a series or sequence of signs. While it is difficult to accept a singular term to define all contemporary art today, altermodern’s expansive definition makes it an attractive possibility. Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art curator, Naomi Beckwith, surmises that the concept of medium as a network is best considered as an attempt to “de-center the artwork, not as the end of a set of aesthetic decisions, but one of the many things that come out of a certain set of processes.” It is shift in classification that appropriately respects the importance of interactive and process oriented engagement with signs in artwork by Roseborough and Smith.

Tim Roseborough is based in San Francisco. Leslie Smith is an assistant professor of painting and drawing at the University of Wisconsin (Madison).

Erica Agyeman is graduate student in Modern Art History Critical and Curatorial Studies at Columbia University.

erica.agyeman@gmail.com

Jolie Laide Gallery Artist Profile July 21, 2010

Certain images are burned into our brains: a pyramid of naked men on their hands and knees, hoods over their heads, overseen by grinning U.S. soldiers; the infamous hooded man in a tattered sheet, standing balanced on a cardboard box with wires dangling from his fingers. These are among the visions left us by the United States’ activities in Abu Ghraib prison, during the early years of the Iraq War. Leslie Smith has absorbed the Abu Ghraib photographs into his imagination and created a body of work that both responds to those events and turns inward from their realities to a more inchoate place.

Some of Smith’s paintings directly reference the cruel inventions of American prison guards, such as “Standard Operating Procedure,” where the human pyramid makes an appearance. Others, like “Dead Weight,” feature what seem to be disembodied feet, reminiscent of the photos of one Iraqi prisoner’s corpse. Still other paintings seem to have originated with these images, but have become more unrecognizable, as in “Peter”, where Smith takes us closer to the realm of the ineffable, charting a course through an array of reactions to our obscene capacity for inflicting pain: stark recognition, efforts at comprehension, and finally, deep internalization.

Profile by Daniel GerwinImage

Some of Smith’s paintings directly reference the cruel inventions of American prison guards, such as “Standard Operating Procedure,” where the human pyramid makes an appearance. Others, like “Dead Weight,” feature what seem to be disembodied feet, reminiscent of the photos of one Iraqi prisoner’s corpse. Still other paintings seem to have originated with these images, but have become more unrecognizable, as in “Peter”, where Smith takes us closer to the realm of the ineffable, charting a course through an array of reactions to our obscene capacity for inflicting pain: stark recognition, efforts at comprehension, and finally, deep internalization.

Profile by Daniel GerwinImage

2009 Yale M.F.A. Thesis Catalogue Essay

At once there is red, then far-too-large crossed legs with a heel kicked up dangling effortlessly, impossibly, a u-shaped teal pipe. Over the thigh a flaccid penis hangs—or is it a nose? Just barely sketched out above this object are the hints of black eyes, the spare white outline of a paper bag. This is an interrogation.

The bag repeats itself, in an earlier self-portrait, with a smaller version of the red nose staring despairingly down at a partially unwrapped chocolate bar. Another configuration places the bag closer to Klan figures, or commedia dell’arte, but with a similar pathetic gesture, innocent yet guilty, hand not quite over the black hole eyes, that red nose, perhaps looking at the pyramid of nudes, scroti hanging.

The bag is a character along with the legs, the pipe, sometimes a white forbidding chair, zippers, underwear, a hand, a foot, yellow, red, blue. How do you best visually articulate power, sex, trauma, which here becomes the soldier – not the violent acts committed, but the return from those acts. Or not even the act, but the birth of the soldier himself, what world he was born into.

This series of paintings by Leslie Smith originated with Abu Ghraib, not just the scenarios, but also the written statements of the detainees. Though that narrative tie might have been displaced, the core questions are still there: how to explicate tragedy–not necessarily against the victims but of the perpetrators? How to allow the interplay of people, the scenario of war, to complicate and be complicated, not just the good and the bad?

A wedge of gums with stolid teeth forced through pipes, yellow again, under a scrim of more yellow–those teeth, that contorted gummy body cannot but come out misshapen.

The bag born into sun yellow fluid, with its appendages: a right foot immobile, a red dead weight, while the left hand agitates to move, struggling against the space, is damned by the barest thread of a green line, the beginning of another series of feet.

And the red painting, potentially the scene before: the bag’s or the soldier’s conception, depicted as an interrogation (of you, the viewer, of the mother, the father, the room, sex, the situation itself).

There is a story thread, but the narrative does not just link together an assortment of objects or appendages as characters, but it is also the canvas itself objectified into a character. The color gives off its own aggressive light. The discomfort here is primary; it is the red, yellow, blue, and the in-betweens that connect the parts. That you connect, as one implicated in the narrative - it is in the gaps that the gestures zing. If this is a soldier, or any man, he is wounded, compressed, and partial before he even begins.

How is someone able to do a tortuous act? Not just beating up another person, but what happens to the person beating, even if it does not leave a bruise? These paintings are the bruise, a blurred line. They force a visceral response. This is an exchange of power, the reality of the mess.

Holly Shaffer Art Historian, Yale University PhD Candidate

The bag repeats itself, in an earlier self-portrait, with a smaller version of the red nose staring despairingly down at a partially unwrapped chocolate bar. Another configuration places the bag closer to Klan figures, or commedia dell’arte, but with a similar pathetic gesture, innocent yet guilty, hand not quite over the black hole eyes, that red nose, perhaps looking at the pyramid of nudes, scroti hanging.

The bag is a character along with the legs, the pipe, sometimes a white forbidding chair, zippers, underwear, a hand, a foot, yellow, red, blue. How do you best visually articulate power, sex, trauma, which here becomes the soldier – not the violent acts committed, but the return from those acts. Or not even the act, but the birth of the soldier himself, what world he was born into.

This series of paintings by Leslie Smith originated with Abu Ghraib, not just the scenarios, but also the written statements of the detainees. Though that narrative tie might have been displaced, the core questions are still there: how to explicate tragedy–not necessarily against the victims but of the perpetrators? How to allow the interplay of people, the scenario of war, to complicate and be complicated, not just the good and the bad?

A wedge of gums with stolid teeth forced through pipes, yellow again, under a scrim of more yellow–those teeth, that contorted gummy body cannot but come out misshapen.

The bag born into sun yellow fluid, with its appendages: a right foot immobile, a red dead weight, while the left hand agitates to move, struggling against the space, is damned by the barest thread of a green line, the beginning of another series of feet.

And the red painting, potentially the scene before: the bag’s or the soldier’s conception, depicted as an interrogation (of you, the viewer, of the mother, the father, the room, sex, the situation itself).

There is a story thread, but the narrative does not just link together an assortment of objects or appendages as characters, but it is also the canvas itself objectified into a character. The color gives off its own aggressive light. The discomfort here is primary; it is the red, yellow, blue, and the in-betweens that connect the parts. That you connect, as one implicated in the narrative - it is in the gaps that the gestures zing. If this is a soldier, or any man, he is wounded, compressed, and partial before he even begins.

How is someone able to do a tortuous act? Not just beating up another person, but what happens to the person beating, even if it does not leave a bruise? These paintings are the bruise, a blurred line. They force a visceral response. This is an exchange of power, the reality of the mess.

Holly Shaffer Art Historian, Yale University PhD Candidate